Articles are starting to appear on the subject. Continuous pricing would lower the price of airline tickets. Really???

For more than 10 years, airlines have been trying to free themselves from the exorbitant costs of the GDS (Global Distribution System) and migrate to a new format, the NDC (New Distribution Capability). The old EDIFACT GDS protocol is gradually being replaced by in-house price and inventory management, with NDC enabling airlines to house their own fares and distribute them more freely.

Change in fare classes and impact on ticket prices

One of the consequences of this change is the breakaway from fare classes. Let’s listen to David Keller:

« Today, in the EDIFACT system, the same air seat is exposed to 26 different fares, depending on when it is booked. (…). Schematically speaking, these 26 fares correspond to the 26 steps (called ‘classes’) of an ascending staircase ».

In fact, today’s many airline fare codes are grouped into fare classes of homogeneous contribution levels (also known as Yield Classes, Buckets or booking classes). There aren’t necessarily 26 of them, but they’re usually not far off. The fare distance between these classes is generally between 5% and 15%, corresponding to the “staircase steps” mentioned above.

Bertrand Flory goes on to explain:

« If I book my ticket today and it leaves the class where it cost 100, I’ll pay 120. With NDC, I’ll pay 102 or 104 or 112 or even, later, 120, but at the last moment, before it goes up to 122 (…). So the price of an NDC ticket is less than or equal to EDIFACT ».

And to drive the point home, Aurélie Duprez of AREKA Consulting asserts:

« We carried out an audit for a CAC 40 company on its top routes in 2023. In 90% of cases, NDC tickets were lower than or equal to EDIFACT tickets ».

The reality of the situation is likely to disappoint many. Admittedly, it is possible that part of the GDS distribution costs borne by airlines today will be redistributed to customers tomorrow in the form of lower fares, particularly in the launch phase. But Bertrand Flory’s explanation seems a little whimsical. Essentially, he’s saying that in the famous fare staircase, a higher step will be smoothed out over a price continuum, leading to a fare cut all the way to the lower step. The optimist therefore thinks that the small rise would actually be a fall.

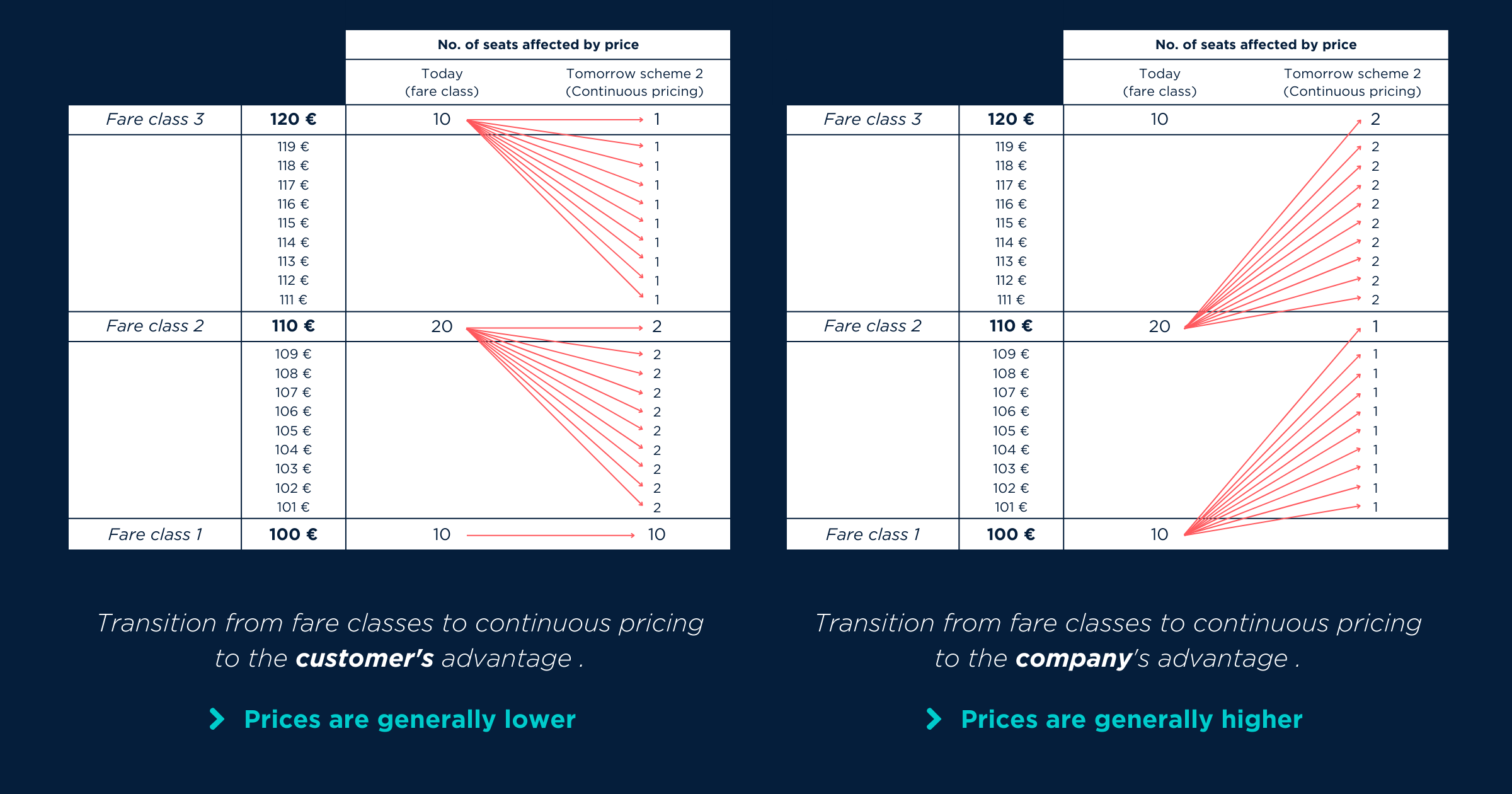

In other words, if 20 customers are expected to pay €100, then 10 more at €120, the author considers that the first 20 will still pay €100, but the 11th €102 (instead of €120), the 12th €104 (instead of €120), etc.

But it’s possible that the mechanism works differently, with small price increases applied to the current run, rather than backdating the next one. In other words, in our example, the first customer might pay €100, the second €101 (instead of €100), the third €102 (instead of €100)… and the twentieth €119 (again instead of €100). In other words, small, continuous tariff increases for all, not a reduction.

Pricing will be managed by the Revenue Management teams. They will use the price in the way that is most relevant to them. No doubt within a controlled average, with as many increases as decreases on lambda flights, more increases on peak flights, rather decreases on off-peak flights.

The future will tell, even if it will be difficult to assess for the outside observer. Only the airlines will really be able to measure it, since the number of tickets offered for sale on each fare level is known only to them. Price surveys, however frequent they may be, won’t be enough to give us an idea.

But let’s not dream too much: prices won’t automatically fall all the time and for everyone. This is not the aim of those who opt for « continuous pricing » and abandon fare classes.

Keywords: Continuous Pricing, Global Distribution System (GDS), New Distribution Capability (NDC), fare classes, fare staircase, airfares, pricing mechanisms, fare management, Revenue Management, airlines, fare decreases, fare increases, price observation.